- Home

- Raymond Harris

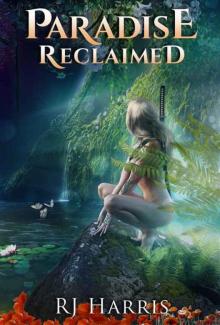

Paradise Reclaimed

Paradise Reclaimed Read online

Paradise Reclaimed

Book one

a novel by RJ Harris

Copyright © 2016 RJ Harris

All rights reserved

1

Nuku

Papatuanuku Teixeira took a slow, deep breath, stood in the full sun and warmed her body. She took another deep breath and stilled her heartbeat. When she was fully oxygenated she leapt off the cliff into the sea. The two heavy rocks that she had tied with reed to create two slings, one held in each hand, guaranteed she sank quickly. When she hit the layer of cold water she let the slings go and the rocks continued into the depths. The cold sent a delicious chill over her naked skin. She looked around. It was as she thought. The cold water was fresh and flowing from an underground river. Its source almost hidden by a forest of long, delicate water grasses.

She swam toward the entrance, the strands of grass caressing her skin, almost entangling her. It was small, just large enough for her to swim in and turn around. She wasn’t feeling any pressure to breathe so she entered. It was much colder now, almost icy. This meant the source of the underground river was snowmelt from further up the mountain. She stopped, stilled her mind and looked around carefully. In the dark she noticed a shimmer of multi-coloured bioluminescence. She swam toward it. This is what she had hoped she would find. The biology of this planet had indulged in a wild experiment with colour, especially iridescence, bioluminescence and colour shifting. She reached down to the flasks strapped to her lower legs and collected samples from the shimmering moss clinging to the cavern wall.

She started to feel the need to breath, but she had four more flasks strapped to her other leg. She swam in deeper, fighting the urge to flee. She filled the last four with more scrapings. She was now fighting the panic response. She turned in the cave and knocked her shin against a sharp rock. She looked down; saw blood and then the flash of a slug-like creature that had obviously sensed something edible. If she was going to panic, now was the time. Instead she turned calmly for the sunlight streaming through the sea grass, her lungs screaming for air, almost at the point of blackout.

Once again she had taken things to the edge.

She broke through the surface and gasped for air, treading water as she re-oxygenated. It was then she felt the pain. She reached down to her wound and realised that the creature had attached itself. Her immediate thought was to try and rip it off but that was dangerous and could lead to a considerable loss of blood. She again fought panic when she realised the current had swept her about ninety metres out. She was in agony as she swam to shore.

She heaved herself onto the rocks and looked at the creature. It was a large sleech and she knew it would not like the heat of the sun, so she made sure it was in direct sunlight. She studied the creature carefully as its system struggled between two competing demands: a food supply and the deadly heat of the sun. The blue stripes running down its repulsive body told her this was a new species.

She waited calmly as the sleech lost the struggle and let go of her wound. She caught it before it slipped back into the ocean and tossed it onto a higher rock, away from the crashing waves. She would add it to her collection. Her leg was bleeding profusely but luckily there was a cure. She folded the leg under her, lifted her hips and directed a stream of urine into the wound. It stung like hell but the uric acid would neutralise the anti-coagulant released by the sleech. She caught some of her urine in the cup of her hand and used this to wash the rest of the wound. As she did so she examined it carefully. Fortunately the cut was not too deep and would not require stitches. There might be a small scar to add to her collection, and an impressive bruise caused by the grip of the sleech, but her main concern was infection. Compared to Earth this planet was relatively benign but it still had its fair share of bacteria, viruses, toxins, venoms and parasites. In this case it was the rot; a bacteria that entered wounds and grew into microscopic worms that gradually turned flesh, sinew and bone into a putrid mess. In the first years people had lost limbs and even died, until a cure was developed from a local plant. When she got to shore she would have to find some bathia leaves with their anti-septic properties to use as a dressing.

For the moment she was exhausted. She lay in the sun, consciously calming the adrenaline pumping through her system and letting the sun help dry the coagulating blood. She thought it had been a successful first foray. With the proper equipment she could stay down longer and go deeper into the cave. If her instinct was right, that particular micro ecosystem could reveal some interesting and valuable genetic variations and biochemical compounds. Some water mosses were rich in micronutrients and some, when dried, made for delicious condiments. But it was the lux genes that were of the greatest potential value for now.

The flash of light woke her from her nap. “Yes, what?” she thought, irritated that her guardian had appeared.

“I’m sorry to interrupt Nuku, but you’ve been summoned to the capital. A section two.”

“Shit.” It was the last thing she wanted. “Okay, yes, yes, affirm,” she said and the point of light folded back into the void.

Request? More like an order, she knew full well that a section two meant that she had to drop all other commitments.

When the blood had started to thicken she carefully packed her specimens into her hand-woven grass satchel and began to wend her way across the rocks to the beach. The jungle beyond provided welcome relief from the heat of the sun. She was fortunate to have had Polynesian descendants and had been born with melanin producing genes. Those settlers with fair skin had long ago had gene therapy to protect them from skin cancer. This sun did not emit as much UV light as old Sol, but it still had a sting and today it was at least thirty-five degrees Celsius with a high UV count.

There was no path through the forest so she relied on her superior sense of direction. She found the bathia plant quickly because it was reasonably common in this region. She picked some of the youngest leaves, easily detected because of their rich purple colour, and squeezed and twisted them to release their antiseptic oils. It stung as she applied the oil meticulously to every part of the wound, twice to make sure. Then she picked one of the larger, red leaves, chewed it to soften it (grimacing at its bitterness) and packed it over the wound. She cursed as she looked around for some yellow reed to create a crude bandage. If she had been thinking clearly she would have picked some first so that it was at hand. Now she would have to hobble to find some - too much movement would cause the bathia paste to fall out and she would have to start again. Luckily it was also common in this region and she spotted some just a few metres away.

When that task was completed she realised she had allowed herself to become dehydrated. She stood still and sniffed. Her instinct suggested there was a creek somewhere to her left, about half a klick. Theoretically she understood how her gift worked, but it still surprised her. Unlike many of her fellow settlers, she had few genetic enhancements: just the compulsory removal of genetic diseases, the enhancement of intelligence and a boost to her immune system. Instead her genome was an experiment in epigenetics. The variation had first been discovered in her maternal great grandmother, Apaotea. Through a natural mutation her basal ganglia was more densely packed with neurons. As the pre-conscious part of the brain it governed instinct. In her family it manifested as a heightened intuition, which, in itself, was simply a pre-conscious intelligence that solved certain problems microseconds before her ordinary conscious mind kicked in and attempted to claim ownership. This meant her reaction time was very quick, her peripheral vision strong and her senses sharpened. The geneticists at the Academy believed that interaction with the planet had triggered an ancient gene sequence and it was her task to master the skill and hopefully encourage more mutation. On a day-to

-day basis she had to learn to trust her “instinct”; to learn not to override her basal ganglia with the rationalisations generated in her prefrontal cortex. Indeed, this had been one of the reasons she had removed herself from civilisation and was wandering naked in the jungle of the Tiangkok peninsula along with the other tribals.

Of course her instinct had been right. The creek had been more or less where the scent of cool moisture had sent her, so she drank, found some nourishing tubers, had a shit, washed herself and rested for a moment. It was still light. Plenty of time left to get back to the village.

She entered the compound as the sun was beginning to set. A group of naked children were sitting under a large weeping tree watching a screen, no doubt being given a lesson by a guardian. Even though they were tribals their parents had not left the Accord, and it required all children to receive the same basic instruction, whatever their circumstances.

She heard a shouted greeting and turned to see a group of adults and older children returning from a successful foraging expedition to the mudflats of the estuary.

“Hey,” she shouted back. “Is that what I think it is?” she asked, noting the large hairless beaver like creature hanging on a pole carried by two of the stronger girls.

“Yep, it was me, I caught it,” shouted one of the girls. “Wrestled it with my bare hands.”

“Should have seen her Nuku,” laughed the other girl. “She was covered in mud from head to toe, even got some jammed up both her cracks.”

The whole group started to laugh. They were understandably excited because the creature was a delicacy and it would call for a celebration.

“What about you?” said a young man. “Successful?”

She lowered her volume because they were getting closer. “Yes, a new micro-ecosystem rich in lux genes.”

“They should call it nuku illuminatis,” laughed a boy.

“Nah, she’s already got three species named after her, can’t be greedy.”

She smiled at the teasing. “Let me store my stuff and I’ll come back and help dig the pit.”

“What’s that?” asked a pregnant girl pointing to her wound.

“Nothing. A sleech.”

She turned up her nose. “Big fucker. Treated?”

She nodded. “Bathia, but I’ll wash it again with anti-rot.”

“Good, nasty stuff rot; it can be infectious.”

“I know. And what about you? You’re a bit far gone to be wrestling mud pig.” The girl was beside her now so she reached out and patted her swollen belly.

The girl held up her hand to show Nuku the stains. “Jelly berries, lots of jelly berries… for the stuffing.”

“Yum,” she said, her mouth watering at the thought.

Later that night Nuku understood why she liked the tribals: a belly full of food, an open fire and good company. Wasn’t this all humanity really ever needed?

2

Akash

Akash Jayarama was ten when he had his first major insight. He was making his way through the tightly packed crowd at the Diwali festival in Bangalore (where his father worked in IT) imagining each person as an atom in a chaotic flow system, when he heard the bang of fireworks. He looked upwards to see the sky burst into a large globe of shimmering lights. He was awestruck.

Later that night as he lay awake in bed, over stimulated by the celebrations, he wondered more about the space in which the fireworks had exploded than the fireworks themselves. They were easy to explain: a matter of chemistry and basic physics. But that basic chemistry and physics could not have been possible without a space or medium in which they could perform their little trick. And yes, he did know that fire needed oxygen to burn, and that the fireworks would fall to earth because of gravity. All that was a given. It was the nature of space that fascinated him.

He couldn’t sleep; couldn’t let go of the problem, so he turned on his laptop, curled up under the covers and searched for anything on dark matter and dark energy.

Akash in Sanskrit means ether. It is a common Indian name, a simple coincidence, although he could not help but imagine it spoke of some sort of destiny.

3

Prax

Praxiteles Smith pulled at the rope to lift the marble block into place. He could have easily attached a levitator but there was something far more satisfying in using pulleys and brute muscle, in sweat and marble dust and the feel of stone. Exertion had its own benefits for the body and technology had made the people of old Earth fat and lazy. His apprentice Cynthia helped him manoeuver the stone into place. Her naked skin was covered in fine marble dust (skin was easier to wash than cloth) and she ignored the small amount of blood seeping out of an abrasion on the knuckles of her left hand – such abrasions were a source of pride for every apprentice stonemason. “Release,” she yelled and Prax gradually released the tension on the rope until the marble slab settled. He then climbed a rough wooden ladder to join Cynthia on the high platform where they used muscle and sinew to remove the rope from the slab and nudge, lever and knock it into place.

“Perfect fit,” he said as he ran his fingers across the join.

“Shall I prepare the next one?”

He nodded. “Three more I think, then a short meal break.” He barely noticed as she clambered over the edge of the scaffold and dropped four metres to the hard ground without harm, the result of her enhancements. There were times he envied her strength but he had chosen other enhancements and it would take years of training for his body to adapt to the new batch of strength genes, so he clambered down the ladder in the old, clumsy way.

When he reached the ground he returned to his worktable to consult the plans on his screen. He looked at a three-dimensional model and turned it on its x-axis. It was perhaps a redundant exercise, and act of vain admiration of his own design. It was a simple building. A new contemplation hall styled like an ancient mosque: a dome placed on a square. The difference was in the carving on the columns and the exterior walls, more reminiscent of the temples of the Indian Golden Age. The floor would be made of several types of stone in the style of Shri Yantra; pink and green onyx, black slate, white marble, jade, jasper, lapis lazuli, polished quartz with veins of gold, all still in plentiful supply in local quarries (it would be a long time before the planet’s mineral resources would be anywhere near being exhausted).

He was a member of the Spanda order, perhaps its brightest star, although that would never be something he would admit. On Earth he might be called a monk, but it wasn’t exactly a religious order. He was a simple lover of wisdom, a philosopher. He had shown an early aptitude for complex reasoning and after his intellectual enhancement his intelligence had soared so that he now sat within the top ninety-nine point nine percentile. There were other citizens much brighter than he, the brightest of all being Tshentso Jayarama, a direct descendant of the Founder. Her intellect shone so brightly that she had exceeded the adjusted scale, which had shifted the old Earth scale fifty basis points (so that the Eden average of one hundred was the equivalent of one hundred and fifty on old Earth). She was playing chess at age one and reading at the age of two. At the age of three she was fluent in six core language groups and their dialects: Greek, Latin, the Romance languages, Sanskrit and its variants, Chinese and its variants and the Semitic languages. She was composing music and was bored by most mathematics. At the age of four she was assigned two guardians to feed her information simultaneously, thus vastly accelerating her education. At the age of five she had demanded full citizenship and was appointed to the Academy. That was two years ago and she hadn’t been seen in public since. He had met her once, at her induction. She was petite and polite, but when he looked into her eyes he was deeply moved. Rather than see a piercing intellect he saw a deep well of ageless compassion. He realised he couldn’t hope to imagine how she saw the world.

That had been one of the problems of Earth. Even though developmental psychologists had demonstrated that each leap of intelligence changed the quality of the way peo

ple thought, the person of average intellect simply thought a higher IQ was about quantity: you thought the same kind of thoughts, but somehow more of them and faster. As the pioneer Piaget had demonstrated with children, stage progression was marked by a distinct qualitative shift: the child began to see the world differently. On Earth they had believed that once you became an adult everyone was essentially the same. This was far from true and it caused a lot of unnecessary suffering. One of the beliefs held by the average intellect was that conformity was a virtue and when those with a higher IQ challenged that conformity, the average intellect acted to suppress them. The history of Earth was filled with examples of geniuses that had been executed, jailed, exiled, or simply denied the opportunity to share their minds because they had dared to question and to dissent.

It was an irrational situation that held humanity back, and at times, actually saw it devolve into periodic Dark Ages. Fortunately there were also times when the ruling elites tolerated difference and these were the Golden Ages; periods of great transformation and discovery: Ancient Greece, India prior to the Islamic invasions, Islam under the Abbasid caliphate, China under the Tang and Song dynasties, the Italian Renaissance, and the European Enlightenment and scientific revolution.

That was why one of the first acts of the Common was to boost the population’s base IQ. And it had succeeded beyond anyone’s dreams. The first shift was achieved simply by selecting settlers with a naturally high IQ. The next shift was a matter of post-partum gene therapy. And given that a high IQ was actively celebrated, this encouraged a further epigenetic shift. The gifted no longer suppressed their talent and this alone lead to an overall lift of at least ten points in every individual. A combination of diet, exercise and pedagogy accounted for the rest. After just two generations geneticists were beginning to see startling mutations that increased neuron density in unexpected ways. It was as if the human genome was making up for millennia of unrealised potential.

Paradise Reclaimed

Paradise Reclaimed